By Kevin Mahnken,

In a study with broad implications for education and perhaps presidential politics, new data indicate that schools in Newark are performing at a much higher level than a decade ago.

According to the report, released by MarGrady Research and funded by the nonprofit group New Jersey Children’s Foundation, academic performance in New Jersey’s biggest city saw huge improvements beginning in 2006, when now-Sen. Cory Booker was elected mayor and initiated a slate of ambitious reforms. Both traditional public schools and charter schools — the expansion of which was a major component of Booker’s agenda — saw significant growth over a 12-year period.

The reforms unleashed political turbulence while they were being implemented, and Booker’s commitment to education reform has followed him on trips to woo Democratic voters in New Hampshire and Iowa, many of whom have soured on charter schools in recent years.

Addressing the controversy over Newark’s disruptive transformation, NJCF Executive Director Kyle Rosenkrans said he hoped the study would showcase the city as a model of change for others to follow.

“One of our key goals is to promote a fact-based conversation about education as it relates to Newark,” he said. “The history of Newark provides empirical proof that you can grow the nation’s highest-performing charter schools alongside a district itself in improvement mode, and there can be a net improvement in outcomes for children. The report speaks to this.”

The study represents the latest data point in the ongoing analysis of whether the reforms — pursued under both Booker and current mayor Ras Baraka, and financed with hundreds of millions of dollars in philanthropic funding — actually succeeded in lifting achievement. It builds on previous research released by MarGrady and Harvard University professor Tom Kane, which found initial evidence of improvements in reading.

To date, the assessment of the reforms’ impacts has been processed through bitter disputes around their origins and implementation. In particular, Booker’s administration has been criticized — by Baraka, among others — for its use of a $100 million donation from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. The massive gift, and the controversy around it, was chronicled in the 2015 book The Prize, in which journalist Dale Russakoff painted a picture of unaccountable technocrats acting without transparency.

Today’s release lengthens the time horizon of previous studies, combing through standardized test scores between 2006 and 2018. It also takes advantage of Newark’s use of the PARCC exam, which allows for comparisons with student performance not just throughout the rest of New Jersey but also in several other states.

In the study, lead author and MarGrady founder Jesse Margolis noted that while the upward trajectory in student scores occurred during a time of dramatic policy shifts, he couldn’t credit the academic improvements to any individual cause.

“We do not argue that any single reform or set of reforms caused the gains documented here,” he wrote, noting the city’s important milestones over the past 12 years, including Booker’s election and New Jersey’s adoption of the Common Core state academic standards. “We simply argue that the gains happened, they are real, and they are meaningful.”

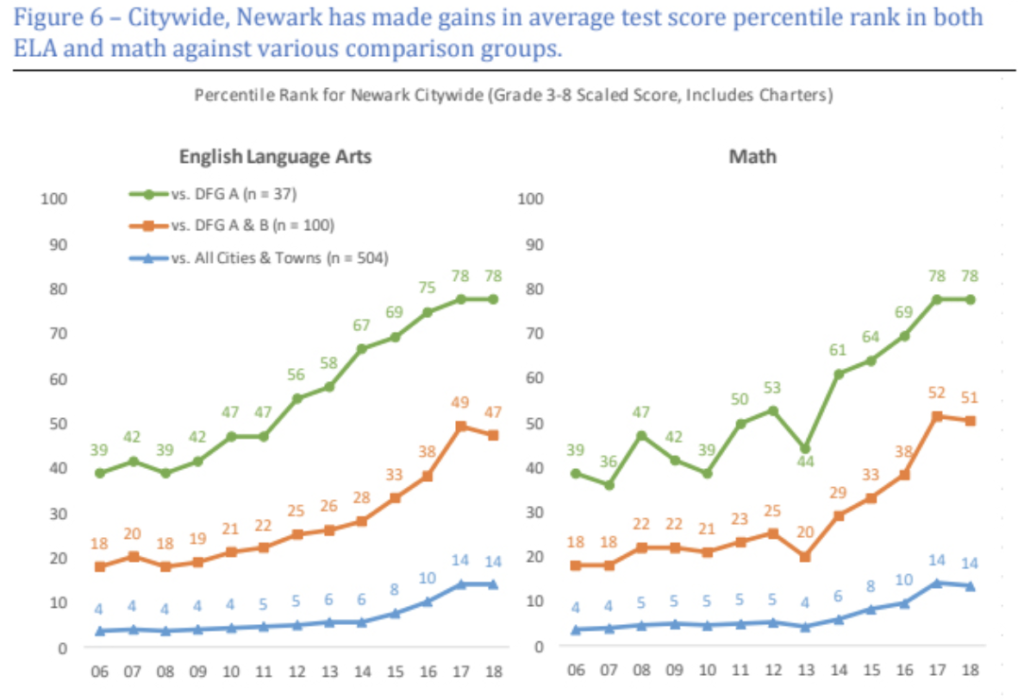

Margolis drew on math and reading test scores for students between grades 3 and 8, including both New Jersey’s NJ ASK assessment and PARCC, which the state adopted in 2015. Over the 13 years under examination, he found steady improvement among Newark schools compared with New Jersey schools as a whole, and much more substantial growth compared with other low-income areas in the state.

For background: Cities and towns in New Jersey are categorized into eight District Factor Groups — essentially swaths of localities that share broad socioeconomic characteristics, such as family income, poverty rate and educational attainment. Newark falls under District Factor Group A, which encompasses the highest-need communities in the state, including Trenton, Camden, Paterson and Atlantic City.

In 2006, Newark students posted average state test scores in the 39th percentile among its peers in Group A; as of 2018, they had risen to the 78th percentile. In order of performance, they had improved from 23rd out of 37 to eighth out of 37.

When measured against the combined cities and towns grouped in District Factor Groups A and B (the roughly 100 most disadvantaged areas in New Jersey), Newark improved substantially in both reading (from the 18th percentile to the 47th percentile) and math (from the 18th percentile to the 51st percentile). And in comparison with New Jersey schools as a whole, Newark improved from the 4th percentile to the 14th percentile in both subjects.

That means that, even after a decade of consistent improvement, Newark still ranks among the lowest tiers of educational performance across the state. In an interview, Margolis said his findings showed that there remained “a lot of room for continued growth” in the city’s schools.

A good deal of the upward movement measured in the study is powered by improvements in the charter school sector, which now enrolls roughly one out of every three Newark students. In 2006, Newark charter students scored in the 14th percentile of New Jersey students in reading and the 11th percentile in math; they now score in the 49th and 48th percentiles, respectively, for students statewide.

In other words, charter students in Newark, a city so beset by educational challenges that its school district was taken over by the state for 23 years, attend schools that fall roughly in the middle of New Jersey’s test scores.

Black students, who have historically attended some of the city’s worst schools, were among the biggest beneficiaries of the citywide improvement. In 2006, just 7 percent of black students in Newark attended a school that beat the New Jersey proficiency average; today, 31 percent do.

“I feel like those gains we look at in the past have come from both the charter sector and the district sector, but some of the charter gains have been particularly impressive,” Margolis said. “The charter sector was strong before; it’s now, if anything, stronger, yet it’s grown to enroll a third of the students in [Newark].”

The organization that funded this research is not divorced from the debate around education reform. The New Jersey Children’s Foundation is partnered with the City Fund, a group that formed last year to raise millions of dollars for reform-aligned organizations throughout the United States. Rosenkrans, NJCF’s executive director, has been tied with charter schools as both a director of strategic initiatives at KIPP and the CEO of the Northeast Charter Schools Network. He also headed a political action committee that donated heavily to a slate of school board candidates backed by both Mayor Baraka and charter supporters.

The study comes at a time when the author of Newark’s tumultuous period of change, Booker, is facing a reassessment of his educational legacy and his relationship with the education reform movement. Margolis notes that, given the senator’s presidential run, “there is … significant national interest in understanding what progress, if any, has been made in Newark’s schools.”

With charter advocates on the defensive among Democrats after decades of general party support, Booker is the presidential candidate most closely tied with school choice — thanks almost exclusively to his time in Newark. In an interview with The 74 last year, Booker defended his tenure as mayor, though he has also stated his misgivings about charter schools in some states, which he has accused of “raiding” from public schools.

The Booker campaign did not respond to a request for comment.